“I play many instruments. Some of them have stories as well”

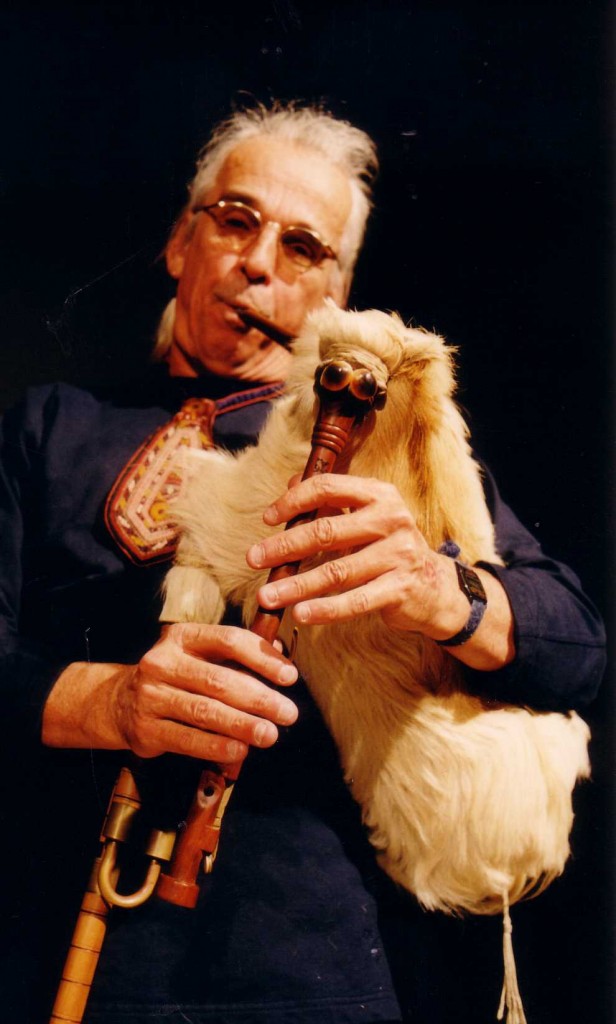

AARDVARK

A hybrid Turkish, Bulgarian, Australian bass bagpipe. There’s only one in the whole world, and this is it. The range is an octave plus a major third. The basic scale is Turkish Ussak scale – like Aeolian Minor with the second flattened by a quarter-tone. The bag is goat-skin. The chanter is made from Cooktown Ironwood and the drone from privet.

A Tale of an Aardvark

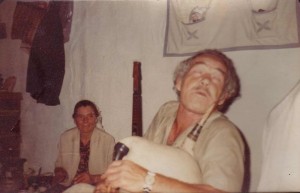

On my first trip to Turkey in 1984 I saw a cassette of gaida (Balkan bagpipe) music in a shop – rare in Turkey. I bought it, and it was fantastic. Guy by the name of Kamil Gül (“Perfect Rose” in Turkish). I thought I might follow it up, maybe score some lessons. I rang the record company to find out how to get in touch: “Dunno,” they said, “We think he lives in Lüleburgaz…” So Linda and I got on a bus to Lüleburgaz, checked into the El Sleazo Hotel, and did what I have done many times on my travels: headed for the local tea-house (or taverna, or equivalent), whipped out an instrument (in this case a gaida) and, played a tune (to establish local street cred). After which I asked if anyone knew Kamil Gul, gaida-player…After a while, someone appeared who had heard of him; but we had to wait for the other guy who knew a guy who knew a guy whose uncle had a car…who arrived in the fullness of time and we headed off to the address. There were wild dogs and other diversions along the way, but we eventually established that he didn’t live there anymore. Dang! Up to this point, everyone had been telling us (as best they could, given that they had no English, and my Turkish was, at this early stage, fairly rugged) that this guy was a Bad Man, a motherf****r, a fatherf****r, who would rob me, rape Linda etc etc, which I was inclined to take with a grain of salt, reasoning that anyone who could play gaida like that couldn’t be all bad…We were eventually taken to meet The Doctor (head of the local hospital), who could speak English (sort of), and who explaıned that Kamil Gül was a very bad man, motherf***r etc etc and advised us not to proceed with our quest. By this time, I was getting stubborn, and dug my heels in. The Doctor was a bit strange. His wife, apparently, had been some sort of Beauty Queen. They had gone to Canada several years before, but had had to return to Turkey on account of her (unspecified) “psychological problems”. He offered us accomodation in the hospital, which seemed strangely deserted…At this point the whole thing felt like it was beginning to turn into a horror movie, so we declined, and took our leave as rapidly as possible.

Next day, it was back on the bus to Kirklareli, near the Bulgarian border. Our man allegedly lived in a nearby village. We needed the permission of the Hamdi (headman) of the village, who actually lived in the town; so we went to his place, and were immediately adopted as Guests, in the sometimes suffocatingly hospitable Turkish manner. The Hamdi couldn’t understand why we’d want to go to all this trouble to meet some vulgar villager. He insisted we stay the night, which we did, dutifully chatting with his Nice family, watching a Nice variety programme on tele before putting on the Nice pyjamas they gave us (we didn’t have any with us in our rucksacks at the time) and going to bed (mmmmm, soft…). Next day we got the 6am minibus to the village (twice daily service) and hit the Official Office. They sent for Kamil (though they still couldn’t understand why we were interested), and eventually dragged him up, unshaven and wondering what the hell was happening, and was he in deep sh*t for some reason?

I introduced myself, explaining that I was from Australia, a gaida-player who dug his cassette, and wanted to talk, have a bit of a blow, and maybe get a lesson or two. He was a little suspicious (as you would be), but after a while loosened up a bit, and invited me back to his place. This did not go down too well with the officials, who could not understand why I would want to commune with this nebish rather than exchanging small-talk with them. Inevitably, he turned out to be a very sweet guy, as was his wife Bedriye, and we had a ball playing and singing all day. It turned out that the Bad Guy reputation came from one of his sons, who had been arrested in the company of a Swedish tourist who had one joint in his pocket (and was serving an “indefinite” jail sentence – he did about 18 months, as it turned out), and his daughter, who, we were told by some old ladies of the village, had “gone to be a prostitute in Istanbul” (not true, as I suspected: She had gone to Istanbul, as I later discovered, but more to escape village closed-mindedness than to flog the bod…She was working as a hairdresser) One thing was for sure: Kamil could play a gaida just like a-ringin’ a bell, and when he was playing he wasn’t in a two-roomed house with dirt floors in a village in Turkey, he was way, way out in Gaida-Land. We had to leave at 6pm on the minibus, but we commuted there and back for three days, and then went to Greece for a festival we wanted to check out, promising to return. This we did, and bulldozed our way through the Polite Hospitality in the town, arguing that Kamil Bey had invited us to stay in his house, and it would be impolite to refuse. They couldn’t get round that one. We stayed a week, I got some lessons and learned a lot of tunes. I was allowed to slip him a few bucks for the lessons (paying for bed and board being out of the question, of course). A magical time was had. The neighbours would cram in, and sing, eat, dance, Kamil and I (and assorted darabukka-players) would play and play… And then we left, and I never saw him again. Back in Australia, I wrote, but they had moved, and I lost touch with them. In 2001, whilst studying in Istanbul, I followed up a very tenuous lead on the daughter, expecting a wild goose chase (had a few of them on the travels!). But to cut a long story short, I eventually did track her down to a town 80 km out of Istanbul on the bus. So (the day before I was returning to Australia), I went up there. Kamil had died three years previously (dang!), but Bedriye was well; and the whole family (five kids, now grown up, of course, including Ruhi, the only one we had met – he was five then. He was now 22, but had gone a bit feral in the meantime, and hadn’t seen his mum for two years… After eating, I took out my gaida, and played, and I had this strange feeling that it was Kamil playing…Ruhi had to go out into the hall for a bit of a cry (and he wasn’t the only one). I was crying too… And that’s the story. He was the wildest, grooviest, craziest, swinginest gaida-player I ever met, and my CD You Can’t Get There From Here was dedicated to him.

Evolution of the Aardvark

Kamil was half Bulgarian, half Turkish and had made his own gaida similar to Bulgarian in construction, but with Turkish fingering and scale. I measured it up as best I could with a school ruler, and sent the measurements back to Australian musician and instrument-maker Linsey Pollak, who had introduced me to the Macedonian gaida many years before. A year or so later, Linsey presented me with his bass version – what a great sound! The drone was a bit of a problem, though.

To make it short enough so it wouldn’t bang on the ground, he had to make the bore narrower than it should have been, which had the effect of making it a bit unstable – it tended to jump around between various overtones. So I figured what I needed was a u-turn at the bottom and some kind of classy spout thingie. This would give the extra length that would solve all the problems. Linsey was too busy, so I asked Craig Fischer, a maker of uillean pipes in South Australia, to do it.

Sure enough, five years later, the new drone arrived (with a loop-da-loop instead of a spout). Fantastic sound, and solid as a rock! In the meantime, I had made a discovery. Many wind instruments have big or little holes near the end, called end-correction holes. They are developed by trial and error, and make the instrument play in tune right at the bottom of the range, where all that stuff you learn at school about sine-waves in tubes goes a bit wierd and doesn’t work any more. I discovered that if I closed the end-correction holes with the inside of my knees (whilst sitting), I could get an extra low note – and a very useful one at that (the 5th of the scale).

I recalled the scene in “Five Easy Pieces” (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6wtfNE4z6a8) where Jack Nicholson, frustrated at not being able to get a serve of plain toast, tells the frowsy waitress in the diner to give him a chicken sandwich, hold the chicken between her knees, and give him the bread, toasted (she was very impressed). So I figured that what I needed was a Nicholson Key to let me close the bottom hole with my little finger (clasping a gaida between the thighs is not easy when you’re playing into a microphone). So I asked another Scottish/Irish pipe-maker, Ian MacKenzie (of Blackheath) to see what he could do, and he came up with a new improved chanter with a Nicholson key. What we now know as the Aardvark was ready to roll. And it wails! Incidentally, many people think it’s called an aardvark because of its appearance. Certainly it is hairy, has a long snout, and two beady little eyes. But it is actually called an aardvark because that’s what you say when your reeds go out of tune in the middle if a gig and make you look like a complete goose: “Aardvark!

KAVAL

Edge-blown wooden flute found in Macedonia, Bulgaria and Turkey. The joints and blowing-edge are made of buffalo horn or composite materials. In Bulgaria they are usually made in three pieces, elsewhere in one piece. They come in various sizes from about 40 to 80 cm.

My favourite is a three-piece Bulgarian kaval in E, made from plum wood and horn. It belonged to the father of my friend and teacher Georgi Doytchev. It is at least 50 years old, probably more, and a beautiful instrument.

I also have a low A kaval. When it finally arrived in Australia (four years and many phone calls after I ordered it in Istanbul!) I discovered it was too long for my little finger to reach the bottom hole, so I asked Ian Mackenzie to make a key. Not orthodox, but it works!

MEY

Turkish double-reed instrument The cylindrical-bore body is made of wood (often plum or apricot) and the reed (“kamis”) from cane, flattened at one end and left cylindrical at the other. The opening at the tip and the fine tuning of the reed are done by sliding the cane ligature (“kiskac”) along the reed. Circular breathing (like with didgeridu) is often used.The brass plug on the side of my instruments is for a pickup – it is a very soft instrument, and on live gigs a microphone can’t cut it without massive feedback.

My meys were made by Ayhan Kahraman in Istanbul, but he is apparently not doing it these days. My current reeds were made by Adem Ceylan, who also showed me how. It’s kinda tricky! Instruments similar to mey are found from the Balkans all the way to China. I have a guanzi from a trip to China in 2005, but I haven’t had time to learn how to play it properly yet.

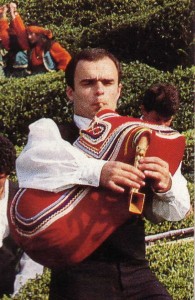

MACEDONIAN GAIDA (GAJDA)

Bagpipe with chanter and single drone, made from wood and horn (or, increasingly, composite materials). Chanter is theoretically cylindrical, but sometimes slightly tapered, according to the maker.

The blow-pipe has a valve to prevent the air from going back out the in-pipe. This is either a leather flap bound onto the mouthpiece, or a disc of leather (or bicycle inner-tube) in a wire cage.

Reeds are single, made of cane. The bag is made of salted goatskin, with the fur on the inside. This skin was made in Australia by Risto Todoroski (see Links Page).

The gaida is tuned by a combination of any or all of the following: moving the ligature on the reed up or down (thereby making the vibrating tongue of reed longer or shorter), putting a little piece of beeswax on the tip of the reed, shaving the reed in different places and partially covering particular holes of the chanter by wax.

The drone can also be adjusted by sliding its three component parts in or out. My Macedonian gaida is from Prilep, in Macedonia. It is made of boxwood and horn. The chanter stock (the bit tied into the bag that the chanter goes into) is from Jack Thompson’s bull Desmo, who unfortunately got stuck in a bog some years ago and drowned. His spirit lives on.

DUDUK

A very old Armenian double-reed instrument with a cylindrical bore, usually made from apricot wood, though plum and mulberry are sometimes used. The duduk is similar to the Turkish mey, but with eight finger-holes on the front, and an extra hole at the bottom that can be closed by pressing against the body. Variants are also played in Azerbaijan (balaban), Georgia (duduki), Iran (balaban) and elsewhere. The duduk is commonly played accompanied by a drone (“dam”), using circular breathing. The duduk comes in various sizes and has a total range of an octave plus a 4th, although the easily usable range is one octave. Mine goes from D to G.

The large double reed (“yegheg” or “ramish”) is made from cane, flattened at one end and left cylindrical at the other. The edges of the reed have pieces of very thin leather glued to them to prevent splitting. The opening at the tip and the fine tuning of the reed are done by sliding the cane ligature along the reed. I got this one from Zafer Tastan in Istanbul in 2008.

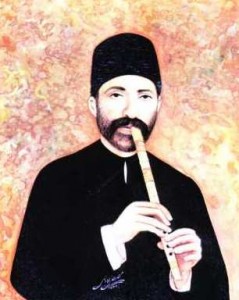

NEY

The ney plays a primary role in the rituals of the Mevlevi (“Whirling Dervish”) and Bektasi Sufi rituals as well as for for Turkish Classical Music. The Turkish ney is distinct from the Arabic and Persian varieties.

The Turkish ney is an edge-blown flute made of carefully-selected cane, usually from Southern Turkey or Syria. The cane must be cut in October/November when the diameter and wall thickness of the cane are most suitable. The cane must be carefully dried and often needs to be heated and straightened as well. The “baspare” (mouthpiece) is made from buffalo horn, ivory, wood or, increasingly, composite materials. Its interior is not cylindrical but slightly curved – one of the skills of the maker. The baspare fits into the “bogaz” (throat) or first section of the ney. There are metal rings (“parazvane”) on the ends of the ney to stop splitting. During construction the ney is tuned not only by placement and size of the holes (remembering that every piece of cane is different) but also by the degree to which the interior nodes of the bamboo are opened. The ney has six finger-holes on the front and a thumb-hole on the back.

Its apparent simplicity hides the difficulty of playing the 53 pitches per octave necessary for playing the complete range of classical makams. Pitches are adjusted by partially uncovering the holes, cross-fingering and changing the angle of the air-stream striking the edge of the baspare. Range is over two and a half octaves. Ney comes in a variety of sizes from the lowest, Davud (lowest note Eb) to the highest Bolahenk (lowest note D). Occasionally smaller neys are found. The neys I am currently playing are by Rifat Varol and Hanefi Kirgiz.

The Arabic nai is similar to the Turkish ney, but has no baspare – the blowing edge is bevelled like the kaval. Blowing technique is similar. The Arabic nai ise usually played in a higher range than the Turkish.

The Persian ney is played using the interdental blowing technique, where the player places the ney in his teeth and upper jaw and directs his breath with his tongue – very difficult!

BULGARIAN GAIDA

The Bulgarian gaida differs from the Macedonian in that it has a “conical” bore. Each maker has his own shape and makes his own tool to bore it. The other dimensions (length, size and spacing of holes etc) are therefore often quite different between different makers. The range is a ninth.

There are seven finger-holes and a thumb-hole. The top hole is very small and is therefore called the “flea-hole”. This hole is used for ornamentation, vibrato and for some chromatic notes.

A lot of ornamentaion is also done with the thumb on the back hole. The original salted goat-skin wore out. This one is tanned, formerly a feral from Percy Island in the Great Barrier Reef, but now a patron of the arts. I got this gaida (in D) through my teacher Georgi Doytchev in Sofia in 1993. It is my favourite – a particularly delicate piece of work. I also have gaidanitsas (chanters) in G, E and D from Traiche Baldzhiev and A and D from Kostadin Varimezov.

BULGARIAN KABA GAIDA

Bass gaida from the Rhodope Mountains in Southern Bulgaria. This one is from Corey Dale who got it in Bulgaria in 2007. I swapped it for a Hungarian duda which Laci Lakk got for me in Hungary on a tour in 1988, and which I’ve never had time to get working and learn how to play.

The chanter and bag are by Kostadin Illchev and drone by Todor Todorv. Wood is cornell cherry and stocks are cow-horn. The bag is goat-skin.

BULGARIAN/TURKISH/ BALINESE/AUSTRALIAN (“GANESHA”) GAYDA

Bulgarian gaida in C (chanter from Kostadin Varimezov) modified by “moving” the fifth hole from the top up a quarter-tone and making the five-fingers-closed hole the tonic (drone) note (A).

(It took me three months to pluck up enough courage to take a rat-tailed file to the hole…) Fingering is similar to Turkish zurna and mey.

I had the front stock carved by I Wayan Sudiarta, a craftsman from Mas in Bali in 2005. It is the Hindu god Ganesh (Lord of Removing Obstacles, Patron of Arts and Sciences and Deva of Intellect and Wisdom). I stained it (except for the eyes and tusks) to match the colour of the chanter. The other stocks, bag and blow-pipe were made by Cory Dale (see “Links” page).

I also use a standard-fingering Bulgarian A chanter with this set-up.

The Turkish gaydas that I play (Ganesha and Aardvark) are different to the other (more common) type of Turkish bagpipe, the tulum. Tulum comes from the Black sea and is similar to the Pontian (Greek) tsampouna, still played in some of the Greek islands. It has no drone and a double-chanter with a curved bell (like a saxophone) at the end, sometimes made of horn but usually from wood. Some of them have very fancy covers. See Links page for video of me playing gayda with Birol Topaloglu on tulum in Istanbul, 2008. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UBimKNUyE_k

TAPAN (aka tupan, dauli, davul, tabla)

Balkan, Middle-Eastern double-sided drum, with a thick skin and a thinner one, played with a big beater and a thin switch. As well as playing its own strokes, the little stick can be placed on the skin, producing a snare affect when the big stick hits the other side.

My little tapan was made by Risto Todoroski. I carved the big stick myself from Australian brush-box. The little stick is plum.

ZURNA (ZURLA)

Known as “zurla” in the Balkans, the zurna is a wooden shawm with double reed.

Similar instruments are found in the Middle East, Central and East Asia, Indonesia and North Africa. The bore is cylindrical till the bell. The reed is traditionally made from a soft reed flattened at one end and tied onto a staple. Circular breathing is used to produce a non-stop sound. Often played in pairs, with one instrument playing melody, the other playing drone using circular breeathing. This technique is also often used on the melody pipe as well. I got the traditional zurna above from Istanbul luthier Yusuf Toraman in 1984.

I also have a zurna designed and made by Linsey Pollak, incorporating elements from the Chinese suona. This allows the normal range of a ninth to be extended by a flat 6th. Linsey also uses reeds made from plastic drinking-straws – less affected by changes due to moisture.

FLUTES:

Saluang (L) is an edge-blown cane flute of the Minang people of West Sumatra. It has only four finger-holes, so a lot of half-holing is done. The blowing technique is similar to ney. Possibly influenced by Arab traders over several centuries. This one was given to me by Sawung Jabo. Another Indonesian cane flute is suling (centre) with a fipple and six finger-holes. This one is a Sundanese suling I got from Agus Super in Bandung, West Java. Hungarian furulya (R) is another fipple flute, with six finger-holes and no thumb-hole (like a tin whistle). It is in two parts, which allows fine-tuning. Laci Lakk got this one (made from wood and bone) for me on a tour in Hungary in 1988.

TENOR SAX

Good ol’ Selmer Mk VI. It’s a bit gnarled now (I’ve had it since 1972) but I wouldn’t swap it for anything. I use an Otto Link 7* mouthpiece with Rico Royal 2 1/2 reeds.